Will cyberspace enable old knowledge to be experienced and expanded or will cyberspace create the the present anew each day, so that there never again is tradition or a past? –Loretta Todd

Over the holiday break, while the in-laws were transporting my family and I to an outdoor light show, I found myself caught up in twitter conversation with colleagues who work in Indigenous literature. We were tweeting back and forth about the reticence, at least comparatively, of scholars in the field to engage with Digital Humanities (DH) methodologies and practices. Indeed, with a few notable exceptions–for instance the work of new scholars like Jordan Abel, Ashley Morford and Alix Shield–Indigenous literature is hardly a footnote in the DH corpus.

I’ve been thinking about this conversation a lot since that night, and as I talk to scholars like Abel, Morford, and Shield, I realize that the conversation needs to happen on a larger scale. I’d like to advance one argument in this post as a starting point for further discussion: Indigenous lit scholars resist DH because the concerns Indigenous communities have about the expropriation of data have not been taken seriously. Those concerns will not be taken seriously until decolonial critique is actively installed at the foundations of DH theory and methodology and settler scholars need to start taking up some of this labour.

While it is usually framed within the context of “new media” rather than “digital humanities,” rigorous and penetrating decolonial analysis of information technologies–written by Indigenous scholars, artists, and programmers–is out there, and its changing the way we think about technology criticism. Transference, Tradition, Technology: Native New Media Exploring Visual and Digital Culture (2006), edited by Dana Claxon, Stephen Loft, and Melanie Townsend, is a collection of essays on the intersections of Indigenous art history and new media practices. Coded Territories: Tracing Indigenous Pathways in New Media Art (2014), edited by Steve Loft and Kerry Swanson, brings together established artists, scholars, and curators, to consider digital storytelling and new media theory from Indigenous perspectives. Just recently, Public produced an issue entitled Indigenous Art: New Media and the Digital (2016) edited by Heather Igloliorte, Julie Nagam, and Carla Taunton, which highlights “the historic and ongoing use of technology by Indigenous communities and artists as vehicles of resilience and cultural continuity.” That’s not to mention the papers being produced by scholars like Jodi Byrd, Candice Hopkins, Elizabeth LaPénsee, Michelle Nahanee, and Karyn Recollet, just to name a few of the folks currently working in the field.

That conversations around digital technologies are drawn around two categories, “digital humanities” on the one hand, and “new media” on the other, is telling in itself. Both fields are invested in similar ideas, they traffic in similar theory, and they advance and engage with similar technologies. Yet DH has only just barely begun to critically interrogate the colonial ideologies upon which its field is founded, whereas “new media” is rapidly establishing decolonial theory as a cornerstone of the work. According to Mohawk scholar Steve Loft, the work of Indigenous new media artists and theorists, “constitute a contemporary manifestation of a centuries-old customary practice and cosmological integrity.” Indigenous thinking, tradition, and innovation plays a significant role in the ways in which media (new and old) unfolds, but new media studies has undertaken the majority of the labour when it comes to unpacking those histories.

But why, you might be asking, do we need to bring identity politics and colonial critique into the digital? Why mess up a space that is, in many ways, saving the Humanities, providing new opportunities for young scholars, and, yes, actively engaging with race, gender, sexuality, and ability? Can’t you just keep your politics over there so we can have this brave little thing over here?

Well, no. And here’s why.

Since its inception, authors, scholars, and engineers have mobilized metaphors of colonization and terra nullius to conceptualize cyberspace. Here’s just one example from a 2000 MIT publication: have a look at the subtitle:

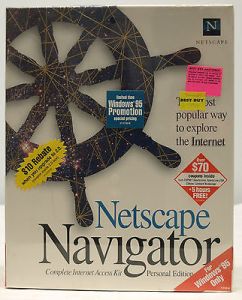

There’s also the branding used by early web browsers, like Netscape, which relied on Columbus era nautical iconography to convey an experience of “exploring” or “discovering” the web:

Or, if you are looking for something just a little more explicit, watch this 1991 documentary from BBC Horizon. Here’s a screen grab of the title card:

These founding metaphors are at odds with the narratives of empowerment that DH so often trades in and, as (settler) DH scholars, we need to be ready and willing to unpack and deconstruct them.

To quote Mohawk artist Skawennati and Cherokee scholar Jason Lewis,

If Aboriginal peoples learned one thing from contact, it is the danger of seeing any place as terra nullius, even cyberspace. Its foundations were designed with a specific logic, built on a specific form of technology, and first used for specific purposes (allowing military units to remain in contact after a nuclear attack). The ghosts of these designers, builders, and prime users continue to haunt the blank spaces.

Building from Skawennati and Lewis, I would argue that of the central issues that haunts DH and makes folks skeptical about the field’s potential for the study of Indigenous literature is data sovereignty: the notion that information should be subject to the laws and protocols of the community in which it is located. According to the US Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network:

Indigenous data sovereignty is the right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership, and application of its own data. It derives from tribes’ inherent right to govern their peoples, lands, and resources. This conception of data sovereignty positions Indigenous nations’ activities to govern data within an Indigenous rights framework.

As an institution, the academy has long been invested in the expropriation of Indigenous data towards the needs and desires of the settler state. The removal and non-consensual dissemination of this data is justified under neo-Enlightenment demands for knowledge and, as Kim Christen points out, the “information wants to be free” mandate of white, liberal nerds everywhere.

But in DH, questions of data sovereignty have circulated around issues of citizenship and the city, metaphors which, in the context of the Indian Act, for instance, work to elide Indigenous presence and reaffirm settler colonial models of enfranchisement. For instance, the computer Science scholar and Visual Arts Professor Benjamin H. Bratton asks of cyberspace,

Could this aggregate “city” wrapping the planet serve as the condition, the grounded legitimate referent, from which another, more plasmic, universal suffrage can be derived and designed? Could this composite city-machine, based on the terms of mobility and immobility, a public ethics of energy and electrons, and unforeseeable manifestations of data sovereignty . . . provide for some kind of ambient homeland? If so, for whom and for what? (quoted in Gold)

It’s the question that Bratton ends on that needs further consideration. Who does networked technology benefit and who is erased, ignored, pushed out in these conversations? What narratives are we privileging when “cities” are held up as the primary modalities of interaction in cyberspace? What does data sovereignty mean when sovereignty itself is governed by a settler colonial force of law?

Tara McPherson astutely asks, “why are the digital humanities so white?” But maybe we also need to ask, “why are settler scholars so invested in DH?”

In the realm of technology, the colonial drive to know, and the demand to have access to any and all forms of knowledge with the touch of a button, is repackaged as “open access”. The idea that “information wants to be free” is dependent on colonial structures of knowing that privilege the dissemination of knowledge over the rights, interests, and well-being of the people it is drawn from. According to Christen this idea,

seems to erase the cultural logics of many groups who view improper reuse and redistribution of their materials as possibly damaging to their cultural practices or traditional knowledge systems. In many Indigenous communities, cultural knowledge is conferred and transferred based on systems of obligation and reciprocity that, while they need not be romanticized as somehow more natural than their non-Indigenous counterparts, should nonetheless be respected and merged into a pluralistic understanding of information’s circulation routes.

Sure, you might be saying, but if we are expropriating data from Indigenous literature, and, by proxy, Indigenous communities, the benefits must surely outweigh the costs, right? I mean, we are advancing the totality of human knowledge here! Setting aside the rather racist notion that the Greeks were the only ones to ever define knowledge and its subsequent dissemination, the nonconsensual circulation of Indigenous data has serious effects on peoples and communities, which should give any good humanist pause. Deidre Brown and George Nicholas provide a pointed critique of the costs of “open access” ideology and the way it impacts Indigenous peoples. According to their research those costs,

may include loss of access to ancestral knowledge, loss of control over proper care of heritage, diminished respect for the sacred, commercialization of cultural distinctiveness, uses of special or sacred symbols that may be dangerous to the uninitiated, replacement of original tribally produced work with reproductions, threats to authenticity and loss of livelihood, among other things.

In short, the nonconsensual proliferation and decontexualization of data has been proven harmful. The legacy of this theft in literature is not subsequent to settler colonialism, it is a founding tenet of settler colonialism. For instance, see the below introduction to American Wonderland, by Richard Meade Bache, first published by Claxton & Co. in 1871:

Indigenous communities have a right to their data and a right to be concerned about the ways in which new initiatives, like DH, seem to brush off their concerns under the promise of new utopias. American Wonderland is a founding example of the settler colonial privilege we need to actively work against. If DH and Indigenous literature are to work together, we need to shift our focus. We need to move away from the idea that DH will allow us to see and read Indigenous literatures in an entirely new way (for what is that insistence but yet a re-articulation of Bache’s racist compliance to “literary form”). We need to move towards holding up Indigenous technologies and Indigenous technologists, because assuming that DH and Indigenous literature are always already disparate categories, assuming that there are not already technologies of “reading” built into Indigenous stories, is to reaffirm the settler colonialist endeavour to erase and replace. To quote Marisa Duarte in her amazing book Network Sovereignty, “in the modern settler imaginary, any Native or Indigenous use of modern technologies was unexpected precisely because Native and Indigenous peoples themselves were unexpected in the subjugated, mediated landscape. They were expected to have faded away like the shrinking herds of buffalo.”

So why have we seen such little work being done in Indigenous literature via DH? Well, its hard to say within any real certainty that the work has been done to make DH a safe space for Indigenous lit. The majority of the decolonial analysis has been laboured beneath the mantle of “new media” and questions about primary issues in the former–such as data sovereignty–go relatively unaddressed in the latter. Furthermore, Indigenous scholars have been left to do the majority of the labour that needs to happen in order for any field of technology studies to be made safe.

While I think that both DH and Indigenous literature could benefit from a more engaged relationship, there are many more conversations that need to be had before that relationship is equitable, let alone desirable. Settler scholars in DH can facilitate these conversations by addressing the historical and colonial contexts of their own work and by citing Indigenous new media theorists in their conference talks and publications. Even better, we can find ways to centre Indigenous scholars in technology conferences, and we can stop tokenizing Indigenous presenters and presentations. We can make sure that Indigenous collaborators are paid fairly for their work and we can recognize the privilege, social and financial, that allows us to work in the fields of technology studies. We can attend to the ways in which technology has historically contributed to the displacement of Indigenous communities and the ways it continues to do and we can call to account the colonialist metaphors that pervade in technology and technology studies. We can put ourselves in service to community, not with a research agenda in mind, not with the hope to test drive a new project, but as a point of access to resources and expertise, if the need/desire for them is there. We can be critical of things like open access and the notion of the commons it rests on. We can work with and for instead of on. We can stop stop trying to figure out how to get more Indigenous folks to DH gatherings and start showing up and supporting Indigenous poetry readings, book launches, and podcasts.

We can ask ourselves, if the digital humanities: for whom? For what?

[…] just come across some important blog essays by David Gaertner. One is Why We Need to Talk About Indigenous Literature in the Digital Humanities where he argues that colleagues from Indigenous literature are rightly skeptical of the digital […]

I also want to point out the early essay by Tim Powell and Larry Aitken “Encoding Culture: Building a Digital Archive Based on Traditional Ojibwe Teachings” and the very good work by Sara Humpreys.

[…] to Talk About Indigenous Literature in the Digital Humanities.” Novel Alliances, 26 Jan. 2017, https://novelalliances.com/2017/01/26/indigenous-literature-and-the-digital-humanities/. Gil, Alex. The (Digital) Library of Babel. http://www.elotroalex.com/digital-library-babel/. […]

[…] Gaertner, David. (2017). “Why We Need to Talk About Indigenous Literature in the Digital Humanities.” Novel Alliances: Allied Perspectives on Art, Literature, and New Media, 20 paragraphs. January 26, 2017. Accessed 20 December 2017. Available at: https://novelalliances.com/2017/01/26/indigenous-literature-and-the-digital-humanities. […]